Wisconsin’s Fox River has been home to native peoples, the main thoroughfare for transporting goods, a source of hydroelectric power, ground zero for the state’s paper industry and is now having a renaissance of recreation and environmental awareness. Today, the 39-mile stretch of the Fox River is home to paddlers, boaters and pedestrians who can watch an engineering marvel in operation.

The river features a system of 17 locks and dams. What makes the system unique is the locks are fully hand-operated and historically restored to their original state when they were built from the 1840s to the early 1900s. All locks are on the National Register of Historic Places.

The system begins at Wisconsin’s largest inland lake, Lake Winnebago, follows the Fox River as it flows north, and ends at the Bay of Green Bay which is the gateway to the Great Lakes. A ten-year restoration effort created a system that is primarily open for navigation to recreational boating and a few commercial barges. Additionally, a multi-year environmental clean-up of the waters has made the river home to flocks of migrating pelicans, bald eagles, sport fishing and flocks of seasonal boaters.

Each summer, thousands of boaters pass through the locks using a seasonal or a one-day pass. Along the way, boaters can tie up at parks and public docks that are a short walk from restaurants, taverns, regional attractions and more.

“All of our communities along the river have turned back to the waterway and are embracing it,” said Jean Romback-Bartels northeast director of the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources and a board member of the Fox River Navigational System Authority, the organization that manages the locks. “Plus the river cleanup now allows the people of Wisconsin to use the river once again for fishing, for recreation and boating.”

Jeff Shari and his family are regular boaters through the lock system. They are long-time residents of the Fox River Valley region, but only started exploring the river more in recent years. “Having the grandkids over to go fishing, swimming, and boating is the highlight of their summer,” Shari said. “When we go through the locks they enjoy helping by holding on to the ropes inside the lock while the water level is raised or lowered.”

The lock system has become a draw for regional paddlers, and the Northeast Wisconsin Paddlers club has seen dramatic growth in their annual Locks Paddle event. Colorful kayaks and canoes pack the locks for the experience and the chance to travel through the system.

“People have a real curiosity about history and the technology of these 1860s navigational aids that can still drop them 10 feet on the river,” said Dave Horst, one of the organizers of the lock-to-lock paddle. “When our paddlers get close from the inside to these time-worn timbers and feel the pull of the current as the lock is drained, it is a cool experience that may send their minds imaging 19th century travel on the Fox River. There are a lot of places we could paddle, but the Fox Locks system is the only place we can give them this experience.”

Lock Construction and restoration

“The locks are a living monument to the immigrants who came here in the 19th century,” said Jeremy Cords, director of operations for the Fox River Navigational System Authority. Waves of European immigrants built the locks and the descendants of those Irish, German, Scandinavian and Dutch laborers call the region home today.

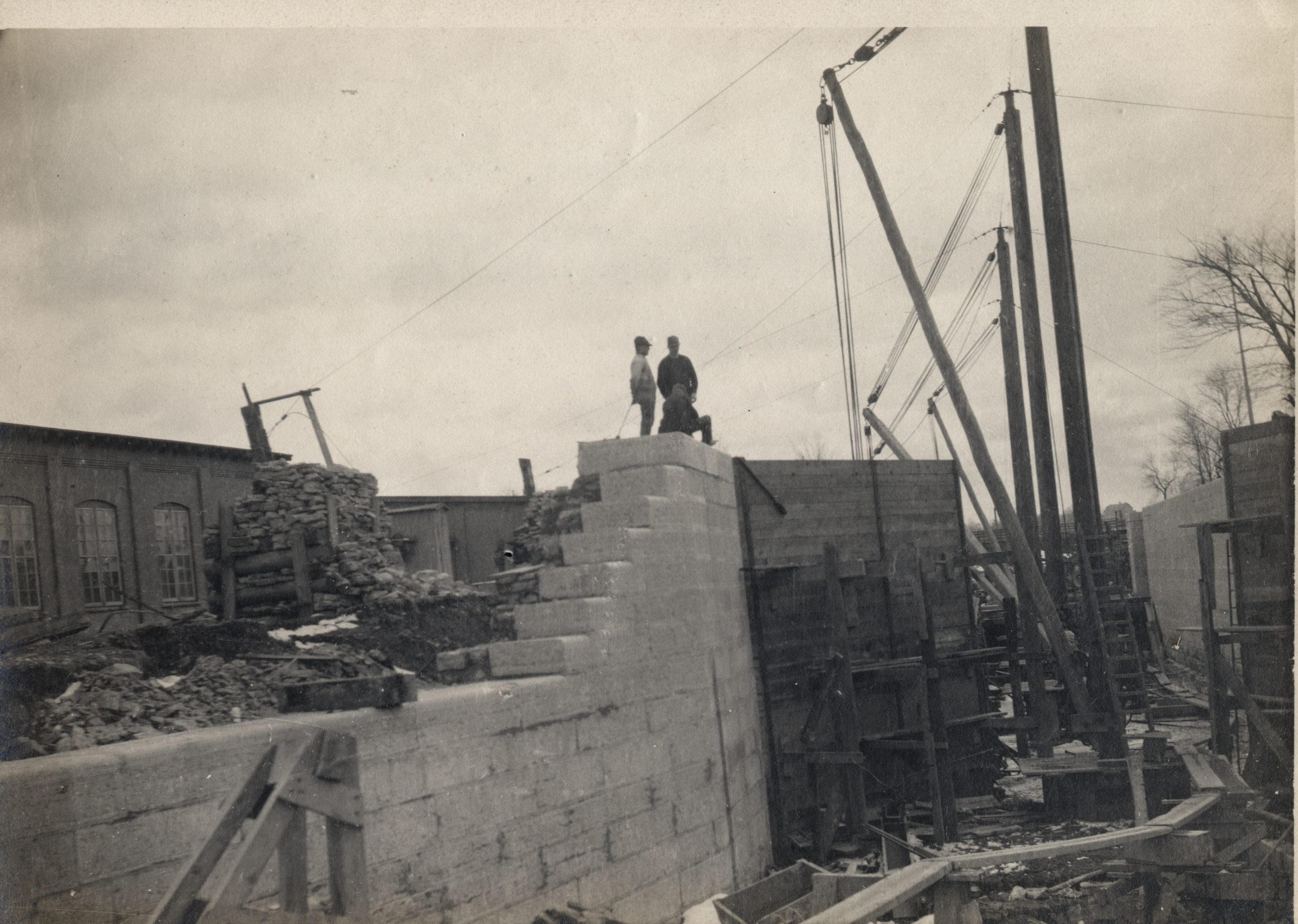

In our computerized world, it’s hard to imagine the locks were built using only manpower, horses, pickaxes, virgin timber, and the stone quarried from the local hills. There are three types of locks on the Fox Locks system: stacked stone rubble, quarried stone and reinforced concrete. Each one represents a specific stage in the evolution of lock construction in the United States. Lock chambers are from 35-36 feet wide by 144-146 feet long and the lift on the system varies from 7.2 to 13.6 feet per lock.

Even more amazing—the locks don’t rely on mechanical pumps or motors. All operation on the system is the result of manual labor and an innovative use of hydraulic engineering.

When a boat enters the lock, the lock tender opens the valves to release pressure so water can enter or exit the lock chamber and water rises or lowers to meet the level outside the lock. Once water levels are equalized, the lock tender opens the lock. It takes about 10 revolutions on the lock tripod to open one side of the giant gates and each lock has four gates. The whole procedure from start to finish takes about 15 minutes.

“Pedestrians can get a great view of the locks in operation from any of the nearby walking trails,” said Phil Ramlet, executive director of the Fox River Navigational System Authority. “But the most amazing view is from a boat. When you’re inside the lock, you can chat with the lock tenders, experience the water level changing, and see the engineering of the system in action.”

Because of the historic nature of the locks, they have been restored according to their original construction. That means wooden timbers used on the massive gates are all water-resistant Douglas fir. Lock tripods, iron valves and gears were restored and, in some cases, completely recast.

Locks are navigable in two sections. The southern portion of the system is open from the City of Menasha to a permanent barrier at the Rapide Croche lock—pronounced rapid-crush. This barrier exists to prevent invasive species from the Great Lakes threatening the lake sturgeon population in Lake Winnebago. The southern end of the lock system features 12 locks, 11 of which are in operation providing 20 miles of navigable river. The northern end of the system features three locks, two of which are in operation. This allows for 19 miles of navigation and gives boaters access to the Bay of Green Bay and the Great Lakes.

Lock History

It all started before the Civil War when congress approved the sale of 150,000 acres of land to improve the Fox and Wisconsin Rivers. Originally envisioned as a route to move military troops, the Army Corps of Engineers recommended a lock and dam system to promote and build the waterway. Construction started in 1846, two years before Wisconsin became a state.

The Fox River drops 168 feet in elevation—this is equal in height to the total drop of Niagara Falls but spread over almost 40 miles. The unique topography is courtesy of the Niagara Escarpment and the receding glaciers that eroded the river basin. The system of locks and dams allowed navigation over the elevation changes made the Fox River the primary route for regional transportation and commerce. In the late 1800s and early 1900s its hydroelectric dams powered the growth of manufacturing, logging and paper manufacturing in Wisconsin.

After decades of neglect, the system was transferred from the Army Corps of Engineers to the State of Wisconsin in the early 1980s, and in 2001 the Fox River Navigational System Authority was established. The Authority is charged with managing and sustaining the system. A major community-based fundraising effort resulted in restoring the locks from 2005-2015 at an investment of $14.5 million.

“This project was more unique because we needed support from local, state and federal governments, plus private support,” Ramlet said. “Our vision is to create a sustainable system that brings value to residents and visitors of our region.”

The system operates from May to early October and charges a modest user fee that is payable online. Public boat launches are available at several marinas and parks throughout the system. For a complete listing of lock locations, hours of operations and fees, please visit www.foxlocks.org.

Lock Tenders

When boaters cruise through the locks today, a friendly lock tender in a bright blue shirt will check their digital passes, secure the crafts, and go about the process of opening valves and massive lock gates. During that time, pleasure boaters and lock tenders trade information about water conditions, boat traffic, and talk about a mini history of the locks.

Roll the clock back to 1900 and the Fox River was jammed with commercial traffic all tooting horns to get through the locks at any hour. When boats blew their horns, there was a saying: “one for danger, two for dock, three for bridge, and four for lock.”

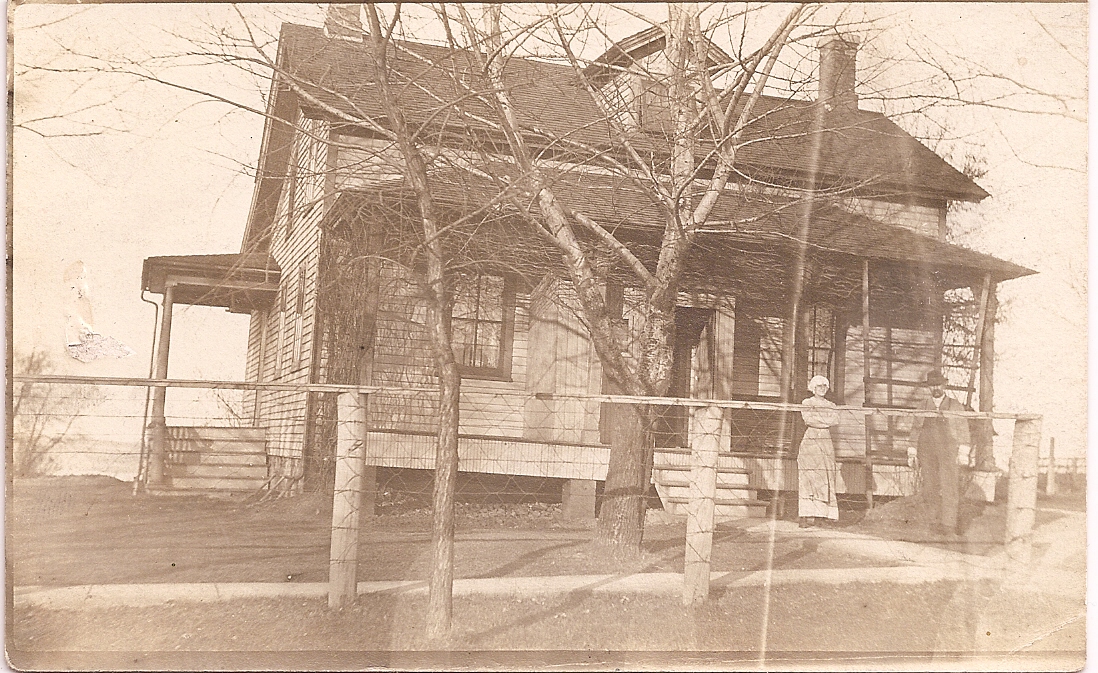

That’s when lock masters and their families lived in homes located at the lock so they were available 24/7 to open the gates. The job required constant availability and lock masters logged the number of boats, cargo tonnage, passengers, weather conditions, and river levels. They were frequently the first responders to recover people or cargo swept away by strong river currents. They maintained the unique mechanisms of the locks and kept the navigation channel open for traffic.

When not on duty, the families of the lock tenders enjoyed the unique home sites and tended gardens, hosted family celebrations, and taught their children to swim in the lock chambers. This was part of a long history of handing lock tender and lock master jobs down from father to son—many of their relatives still live in the region today.

Pat Spaay is retired from the paper industry and a fill-in lock tender who grew up near one of the Appleton locks. He remembers a childhood spent on the locks. “When we were younger, we were a pain for the lock master because we would jump in the river and swim near the lock doors. But his wife was nice and would give us cookies,” Spaay said.

Today the lock tenders are seasonal employees, but many are well-versed in the history of the locks. “Today’s lock tenders are part of the continuing history of the lock system and many of them grew up as friends or relatives of the lock masters that worked here in the 1950s,” said Jeremy Cords, director of operations for the locks.

It takes about 20 lock tenders to manually operate the locks during a navigation season and many are college students or retirees.

Mary Schmidt is a 40 year veteran of the communications industry and a happy resident of Wisconsin where she regularly enjoys the state’s natural resources. Although she is not a boater, the lock system on the Fox River is her passion project. She may be reached at mkathrynschmidt@gmail.com