I mention this because I regularly give classes and talks on boating safety and a question I love to ask when it comes to fueling is: What’s the first step to take? The answers run the gamut from proper venting and bilge blowing to guarding against static electricity by placing the hose nozzle against the fill opening. All correct, but not the first move, which is making sure the boat is properly secured to the pier.

Nobody expects to hang out on a fuel dock, so the inclination is to tie off quick and simple. Resist that thought. It might take a bit longer, but go the whole route: bow and stern lines, and springs. Most fuel docks are exposed to whatever comes down the pike, including wind and wave action, as well as passing boaters. Rock and roll might happen when you least need it.

A Breath of Fresh Air

Now, venting the bilges — especially for gasoline-powered boats — seems to be as basic as it gets. We all know the procedure: open all ports, doors, windows and hatches and run the bilge blower for at least five minutes after fueling. On smaller boats, where it’s practical, just throw open the engine cover or bilge hatch and you know there won’t be any lingering fumes. Also, it’s nice to look at the engine as it runs for a few minutes, because you just might notice details that you weren’t aware of before, like a spray of fluid, a wobbly belt, or something that doesn’t smell or sound right.

Since the advent of fuel injection, however, I’ve noticed that among some boaters, bilge venting isn’t looked upon with the same seriousness as before. One guy told me that since a fuel-injected engine, unlike a carbureted engine, operates on a closed system, venting isn’t necessary, as the engine won’t start anyway if the system is breached and air is introduced. That’s not true. Gasoline that flows through a fuel-injected engine is the same volatile stuff that runs through a carburetor. It, or its fumes, can end up in the bilge, which must be vented.

Outside the Lines

Of course, diesel isn’t nearly as combustible as gasoline. But I don’t see a problem with following the same procedure. The stuff stinks, and a good venting will remove any residual stench.

A diesel fuel system is truly a closed one, and if air is introduced the engine, it will not run. But diesel engines have return lines — hosing that returns excess fuel to the tank after it passes through the system. On more than a few occasions, I’ve seen or experienced a rupture of a return line while the boat is under way. These lines are rarely serviced; they’re usually routed where they’re not easily visualized, and they’re subject to vibration, chafe and trauma. Therefore, they break. And when they do, because they’re out of the closed loop of the system, the diesel engine will merrily keep running, all the while pumping fuel into the bilges.

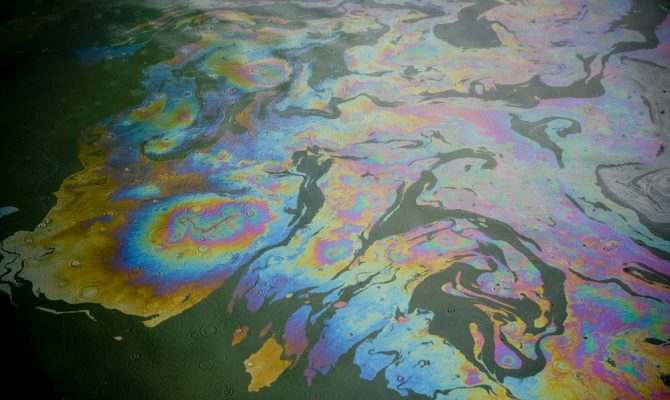

OK, the odds are that you won’t have an explosion, but fire is a possibility. Depending on the configuration of the boat, the sloshing fuel could come in contact with electronic components or possibly the hot exhaust of the mains or a generator. At the very best, you’ll have a big, fat mess down there — not to mention a big, fat fine when the bilge pump does its thing.

I know of diesel boat owners who don’t even know they have return lines, much less where they are. When a malfunctioning line does announce its presence, though, you’ll never forget it.

Pardon the pun, but if you’re not fuelish when it comes to fueling, chances are you’ll live to fuel around some more.

Author: Stu Reininger is a regular contributor to HeartLand Boating